Tabang

Where could we find pristine rain forest? So far our visit to Kalimantan had been disappointing. The scarred grasslands and logged-out forests of the coastal lowlands were depressing. Kutai National Park was a mess. There was no more accessible pristine forest near the lakes around Tanjung Issuy. A guide we had met in Kutai mentioned that near Tabang, upriver from Kota Bangun, we could still find “big trees”. Logging had already penetrated far up the Mahakam River, but this area, on the Belayan River, was still pristine. Our guidebook, devoting only a few lines to Tabang, mentioned that it might be possible to trek in the area.

|

|

It took us two days to travel from Kota Bangun to Tabang. The first day we chartered a boat to take us two hours upriver. From there we hitched a ride on a truck delivering fertilizer to a palm-oil plantation. We stayed overnight with some of the employees at the plantation. The next day we chartered a speedboat and then a longboat with an outboard motor to take us the rest of the way, arriving in Tabang just after dusk. The inhabitants of Tabang were coastal Indonesians. They advised us to look for guides at Long Lunuk, the Dayak village further upriver. Even there it was difficult to find what we wanted. The village school teacher (the village head was absent) took us to meet Lebi'ing, a smiling, slightly pudgy Dayak with a bushy goatee. He offered to take us upriver to his family's rice plantation for some hunting and fishing. We instantly took a liking to him. After working out a price for the boat, fuel and food, we agreed to depart later that morning.

|

|

It sounded like a wonderful opportunity, especially the wild pig hunting. The Dayaks are formidable woodsmen, skilled with machetes, spears and blowpipes as well as with boats and nets. Lebi'ing brought his brother-in-law, Ding, and his son, Octopianus. Ding was a long-haired, dour-faced muscular he-man of the jungle. He talked in grunts and monosyllables. Octopianus, or “Nus”, 13 years old, was skilled with the boat and in the forest. After loading, we pointed our boat upriver, following the wide Belayan as the forest became thicker. We turned up a side branch of the river and the forest got better. We began to see more tall trees and other signs of healthy forest canopy. We shot rapids with the boat, breaking an aluminum propeller on the rocks. Luckily we had brought several replacements.

The family “pondok” (hut) was a small bamboo construction on stilts in a recently cleared area along the side of the river. Several families shared the clearance, each with a collection of dogs and chickens. Behind the pondok, a patch of forest had been chopped down and burned. Tiny rice plants, next year's crop, sprouted in the dirt. Inside Lebi'ing's hut were sacks with last year's harvest: enough to last the family through the season. The water ran clean and dark. There were no villages or permanent settlements upstream. Ding drank the water straight from the river.

|

|

That afternoon, Ding took us in the boat with the throw-net and caught a whole basket of fish. Perched on the bow as we drifted downstream, he crouched, waiting for the perfect moment to throw. When the net came down, Nus dove into the lukewarm water to retrieve the entrapped fish before they could wiggle free. We ate them for dinner, fried in pig fat, along with a pot of tasty dryfield rice. It was quiet at night. We lay on the raised floor of the hut, listening to the chickens clucking below as they foraged for scraps, and talked about Dayak traditions and culture by the light of an oil lamp. The next-door neighbor came over to talk. He had hiked the trans-Borneo trail from the headwaters of the Mahakam to the villages above Putussibau on the other side of the “continental divide”. The only disadvantage of living in the hut was the cockroaches. At night they crept out of cracks and crevices in the bamboo poles and bark ceiling. They dropped from the roof and scurried across the floor. Tolerance was our only option. We covered our heads while we slept to keep them from falling into our mouths. After having slept with so many, Anne is now much less squeamish about roaches!

|

|

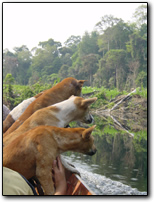

Lebi'ing, Ding and Nus took us hunting several times. Taking their spears, they called the dogs in a long, yodeling cry. The dogs, excited by the hunt, rushed down to the riverbank and leapt into the boat. Ding threw the smaller dogs, yelping, back onto shore. They were too small to hunt and it was dangerous: a wild boar could injure an inexperienced dog. As we moved upriver, the dogs strained into the wind, leaning over the side, their noses sniffing for a trace of scent. We looked for a place where a smaller stream joined the river. As we glided to the bank, the dogs jumped off and bounded into the forest, yapping, while we walked upstream listening for the barking that would indicate that they were on the scent. The Dayaks walked barefoot into the forest, armed only with long spears and machetes. During our first two excursions the dogs did not smell anything and we eventually had to round them up and take them home. On our third try, a late afternoon, Lebi'ing said he was too tired to come. He sent us with Ding and Nus.

|

|

Right away when we landed the dogs charged up the streambed. Soon we heard distant barking. Ding motioned us to follow as he ran lightly over the rocks, dodging vines and brambles and leaping over fallen logs Soon he was out of sight. Nus stayed with us, but, hearing the intensity of the barking, urged us to hurry. Rattan vines ripped at our clothing. Eric ran ahead, slipping on the smooth stones, running as fast as he could in his Tevas. Anne was already far behind when Nus pointed to something ahead. A large white boar with a grey bristly back and long, upcurving teeth was standing in a pool of muddy water, surrounded by barking dogs. It rushed forward to goad the dogs, which dodged the attempts and renewed their posturing and barking with vigor. Nus pressed his machete into Eric's hand and advanced with his spear. From behind a bush, Ding, spear in hand, crept slowly up to the pig. Suddenly, with full force, he rammed the spear straight into its chest. He heaved his weight into the spear, pinning the pig into place, and began kicking water in all directions to distract it and to keep the dogs at bay. He drew his machete and with one blow severed the back of the boar. The dogs leapt on the fallen pig, whining as they tore at its tough skin. Ding quickly cut open the belly, pulled out the stomach and intestines and left them under a rock. Nus cut a long, straight sapling and Ding stripped off the bark. Working in the fading light, he cut slits in the pig's skin and threaded the bark strips through the holes to create a “pig backpack” to enable him to carry the carcass back to the boat.

|

|

When we got back to camp, Ding sat on the riverbank and hacked up the pig with his machete. Neighbors on their way upriver were given a leg and part of the ribcage. The rest of the meat was chopped into pieces. Every part of the pig was mixed together. We skewered hunks of meat on bamboo sticks and roasted them over the fire. Slabs of fat and the leftover inedible bits were fried to extract the grease, a prized cooking ingredient. Ding extracted the teeth from the pig's lower jaw and presented them to Eric. Sitting lazily around the fire, our stomachs full of meat and rice, Lebi'ing talked of the old days, before outboard motors, when Dayaks still hunted each other. As a child he learned never to sit while eating but to squat, in case their camp was raided.