Wusarem to Wet

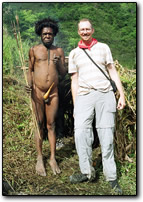

The next morning, Romy cooked rice for breakfast. We decided to make enough to eat a hot breakfast and a cold lunch. By sprinkling “abon sapi”, a spicy, crunchy condiment, or drizzling some sweet soy sauce over it, we could make the cold white rice palatable enough to get down. From Wusarem we climbed a steep trail through the forest, emerging on a ridge with a view of the surrounding countryside. The hot sun had just started to burn off the morning mist. A man dressed in traditional costume emerged from a small shelter by the side of the trail. Holding his wooden bow and arrows in one hand, he gestured for a cigarette with the other. We gave him a couple of cigarettes, and examined his arrows. The points were wooden, bound with rattan to the bamboo shaft. New Guinea had never invented feathering to stabilize an arrow’s flight. Each type of prey had a different arrow. Three- and four-barbed tips were for birds. Twin barbs were for couscous and “tikus pohon” (tree kangaroos). Single-barbed arrows were for pigs, or, during outbreaks of tribal warfare, humans.

|

|

We continued walking, and after another steep climb we arrived at a grassy pass. Here was another Papuan, with clothes, carrying a string bag. He seemed friendly, so we gave him a cigarette. He accepted it graciously, then gestured for a light. While Anne rummaged around in her pack for matches, he showed us his “lighter”, a loop of rattan and a forked stick with deeply cut grooves. Smiling, we encouraged him to give us a demonstration of fire-making. Barking out orders to a small boy nearby, he gathered grass and flower buds from the damp hillside. He rubbed the material between his hands to dry it, then carefully constructed a bed of thicker stalks on the ground, with the softer, more combustible buds on top. The boy returned with more dry chaff to add to the pile. After looping the rattan around the wooden shaft and placing it on the pile of material, he held it between his feet while pulling the rattan lead back and forth against the wood. Soon the pile was smoking, but then the rattan broke, and despite his gentle blowing on the pile of tinder it was not enough to start the fire.

|

|

The trail now climbed higher into the mountains. The river receded into the distance below. The sun came out behind the clouds and burned with intensity. It was easy to get sunburned at this altitude. We stopped to eat lunch near a pair of women with string-bags sitting on the trail, and gave them our leftover rice. Before leaving, we bought some fresh ginger from them. A man stopped to cut some bamboo to restring his wooden bow. Afterwards we entered a thick cloud forest, the vague shapes of giant trees looming in the mist. The muddy, slippery trail was made of felled logs and branches. Strange-looking palm trees, like something out of a Dr. Seuss cartoon, rose on stilt-like roots along the trail. Romy had a problem with his knee, and had to walk slowly.

|

|

We arrived in Wet just before it started to rain. A crowd of children, some with distended stomachs, gathered around to stare at us. None of them had shoes. Several had no clothes. We established a good rapport with the schoolmaster, and spent a long time around the fire discussing Dani culture and traditions. The big pot of instant noodles that we cooked for dinner went mostly to the villagers. The children wolfed down the food, licking their plates clean. One boy, about three years old, lay down on his mother’s lap and grabbed at her chest. She sat him down and took one of her large breasts out of her T-shirt. The boy lay on his back, watching us, happily sucking. The Dani will nurse a child until four or five years old, and only after the child is weaned does the husband have the right to sleep with his wife again. This was one of the reasons why the men often had more than one wife. One man sitting around the fire claimed that he had four wives. He said that it “cost” between three and six pigs to marry. In the highlands, the men of a clan sleep together in a special hut called the “honai”. The women sleep together with the children in their own huts. Romy slept by the warmth of the communal fire every night in a honai. Although we were interested in trying it, we were put off by the cramped, smoky interior. The honai teems with pesky insects, as pigs often share quarters with the humans. A missionary we had met showed us the bites he had received after just one sleepless night. After a month of furious scratching, they still looked fresh.

|

|